I’m at Intel’s Extreme Masters e-sports event in Sydney playing a game called Beat Sabre. Wearing a headset, in virtual reality I slice small cubes thrusting at me at an alarming rate, in a rhythm.

In what seems like a VR version of Fruit Ninja set to music, I kind of dance on the spot.

Indeed, I’m told that VR dancing will become an e-sport itself. The game was released just two days beforehand and, to commemorate it, Intel flew out creator Vladimir Hrincar from the Czech Republic.

Playing interesting new VR games is one of the side events at Qudos Bank Arena before the main event in the stadium later that day, an elite international games playoff between 16 invited teams playing Counter-Strike: Global Offensive, held across three days.

With an hour to kill before game play, I head to a big darkish room where gaming enthusiasts are spending big money buying the latest high-end gaming componentry: cases, processors and graphic cards.

It instantly reminds me of the tech scene 20 years ago where, at markets on a Sunday morning, do-it-yourself types would scoop up cheap components to build home PCs. But this is high-end stuff, hardware nirvana for gamers.

“Many of the people who play e-sports want to have the best PC they can buy, so many of them want to upgrade as they go,” explains Glen Boatwright, Intel’s development manager, ANZ channel, who accompanied me.

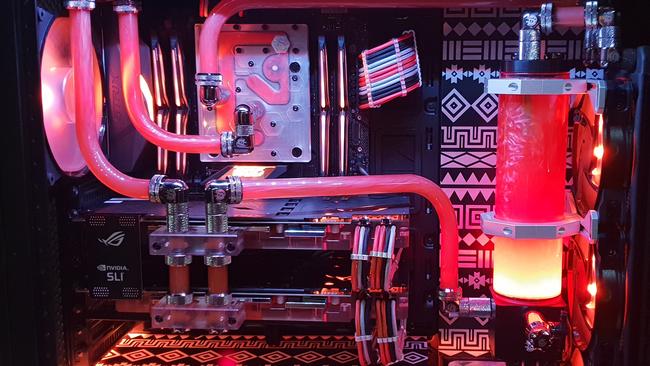

And there’s beauty with brains. The room is dotted with computers in transparent boxes containing meticulously arranged components that light up like Christmas trees.

Boatwright explains that beautifying gaming PCs is called “modding”. “People spend hundreds of hours doing this to your PC like you would a car.” To me it’s like a hi-tech, 21st-century version of a prize bull judging at a 1900s agricultural show.

Then I encounter the overclockers, a tribe of people skilled in tweaking a computer’s setting to make its processor run very fast, to aid gaming dominance. But there are risks. Overclocking increases heat output and shortens the lifespan of components.

Professional overclockers such as Dino Strkljevic take overclocking to the extreme. As they ramp up the processor speed, they pour liquid nitrogen over components to keep them cool. They also have a blowtorch handy to quickly reheat the processor if it’s about to freeze. I’m watching a nailbiting exercise.

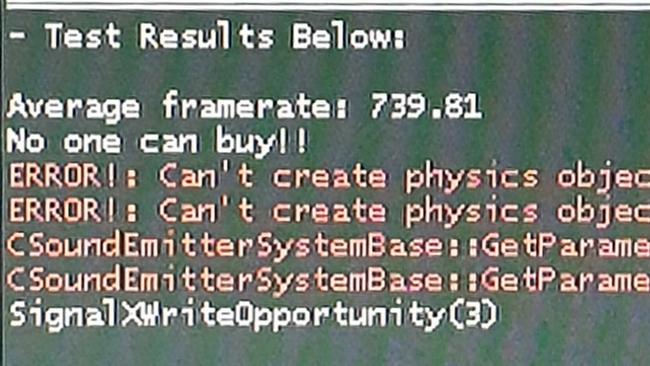

As I look on, Strkljevic achieves an astonishing 739.81 frames per second video from an overclocked processor, which is insane when you consider everyday video plays at 24 to 30 frames per second. The computer’s temperature was only minus 124C.

Eventually it’s main game time inside the stadium. There’s the build-up as competing teams are announced, and cheering as these international gaming doyens appear on stage. There are the ums and aagh’s as CS: GO gets under way, and cheering when one team makes a breakthrough, mowing the other down in gunfire. The atmosphere is like a football final.

Here audience members are overwhelmingly millennials, although e-sports isn’t a new phenomenon. What’s new is its migration from online to exhibition centres, and now to an epic stadium event.

Games media intelligence firm Superdata cites revenue of $US1.5 billion ($1.99bn) last year and estimates an increase of 26 per cent by 2020.

Intel’s global marketing e-sports and gaming strategist, Brenda Lynch, says the new gaming genre is booming.

“Competitive video game play has always been around for about 20 years, but it has transitioned into a stadium event,” she says.

“One of the big inflection points that happened a few years back was the introduction of the streaming platform Twitch as well as other distribution platforms.”

She says high-powered technology brought the ability to stream gaming in real-time. “Those technologies helped burst the growth trajectory of the sport.”

As the fan base grew, leagues such as ESL (the Esports League, which Intel partners) have begun to move from hosting exhibition-style events at trade shows and in hotel suites to arenas.

Australia held its first arena-based Intel Masters Tournament last year. It attracted more than 15,000 fans at the venue and an online audience of eight million. “It’s really great numbers,” Lynch says.

Overseas, both the live and online audience numbers are astonishing. The biggest of the Intel Extreme Masters, held in Katowice, Poland, drew 170,000 people and 40 million to 60 million viewers online. Lynch says e-sports is especially big in the US and eastern Europe, but there are tournaments in western Europe, Asia and throughout the Americas.

“There is no barrier to entry. You can be any age, any sex, any colour, race, religion — nobody cares about those things. It’s about how you play the game.”

Different franchises offer different games such as League of Legends and Rocket League. Some teams specialise in one game; some organisations have different teams playing different games. It seems Fortnite is the latest craze.

Australia has a reputation for punching above its weight. A US-based Australian team called the Renegades played in the Intel’s Sydney event but was eliminated.

One interesting development is the growing link between conventional sport and e-sports.

Last year the Adelaide Crows AFL team signed up Sydney-based Legacy Esports, a professional team competing in the Oceanic Pro League. Recently, another AFL team took an interest in the masters.

With lots of money to be made, sporting teams see the potential of drawing supporters into an e-sports venture. In soccer, there’s now an e-sports-based FIFA game. Last year the Sydney Cricket Ground announced Australia’s first e-sports high performance centre, a new home for League of Legends Oceania champions the LG Dire Wolves and female development team Supa-Stellar.

Intel says Newzoo research estimates an audience of 386 million people watching and participating in e-sports and 16 per cent growth per year by 2020. The millennial demographic dominates the market but people of all ages watch and participate.

The growing number of e-sports leagues and different events last year saw formation of a local peak e-sports industry body, Esports Games Association of Australia and New Zealand.

Board member Daniel Chlebowczyk, a former professional gamer working at Double Jump Communications, says the association aims to represent and assist teams, players and organisations. “It’s still a relatively young industry. Players may not know about expected standards of behaviour and events may not know about each other,” Chlebowczyk says.

“There is a movement among universities and its administrators to engage with e-sports; how do they go about it.”

More local events are in train. Mr Chlebowczyk says Battle Arena Melbourne takes place this weekend with two major Esport leagues: A Capcom Pro Tour Ranking Event with Street Master V and a Tekken World Tour Master Event with Tekken 7. He says Gfinity is about to launch its Gfinity Elite Series in Australia across three e-sports titles.

It’s not only the big computer companies with lots to gain. HyperX, which makes low latency gaming keyboards and headphones, says it’s sponsoring more than 30 e-sports teams around the world.

Susan Yang, HyperX marketing director in the Asia-Pacific region, says recent studies show that e-sports is on the track to become the next mainstream entertainment in near future. “HyperX has been partnering with NBA teams, players, e-sports leagues, and now bring the same experience to our collaboration with Sydney Swans teams and players,” she says.

Indeed, a potent mixture of passion and money suggests e-sports has an enormous future.

Published in The Australian newspaper.