Meet Chuck and Diane. For a week, they were my constant companions. Wherever I went around Sydney, so did Chuck and Diane. But this wasn’t a sightseeing tour.

Chuck and Diane are not people, but two Android smartphones. They came loaded with special software, which fed me exactly the information the phones are sending to Google throughout the day and night.

I was snooping on Google snooping on me. Payback. And very relevant too, given the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s expose of the inadequacy of our privacy laws, in part of its report released last Friday

But we don’t even begin to understand just how much personal data is being taken. We can’t even keep track of it. We need a privacy reset button.

I’m not just talking about Google and Facebook working out what I intend buying, and serving me ads about them. I’m not just talking about information gleaned by cookies monitoring websites. It’s a deeper analysis of my whereabouts than simply a record of location on Google Maps.

Data fire hose

READ MORE: Hey, Siri, call me old-fashioned but you can leave us alone now

It’s a relentless collection of data gleaned from your Android phone: where you are, the identification of cellular towers and the identification by ID (Mac address) of every wi-fi access point you encounter, constant recordings of barometric pressure — Google seems to want to know which floor of a building you are on — and your state: whether you are still on a bicycle, or in a car; your longitude, latitude and speed, and an estimate of data accuracy.

Location data was collected even though I had Google Maps location history turned off during this test.

Wi-fi access point records include frequency and strength. This is something more than commerce, activity and health data. It’s surveillance on a scale few users are aware of.

Google says it uses location information to deliver better results and recommendations on Google products, with a user’s permission. Location history is opt-in, and you can edit, delete or turn it off any time, Google says in a statement. The company says it offers users control over their data through the My Account site.

Over the one week of testing, Chuck and Diane sent a fire hose of data to Google, which the phone software intercepted and sent to our analysis program.

I kept a diary of my activity for that period to match it against Google’s data stream. Here are some examples.

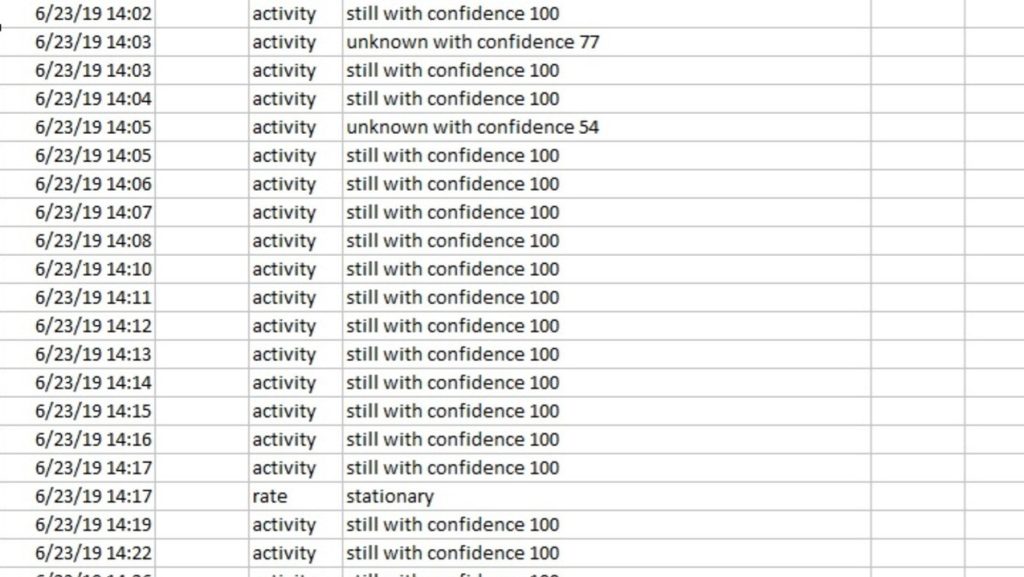

Between 2.02pm and 2.33pm on June 23 — 31 minutes — one of the phones conducted 39 wi-fi scans, 15 locations scans, 15 barometric readings, and 24 activity scans — whether I was still or on foot. More than 20 of the wi-fi scans each identified more than 20 wi-fi access points.

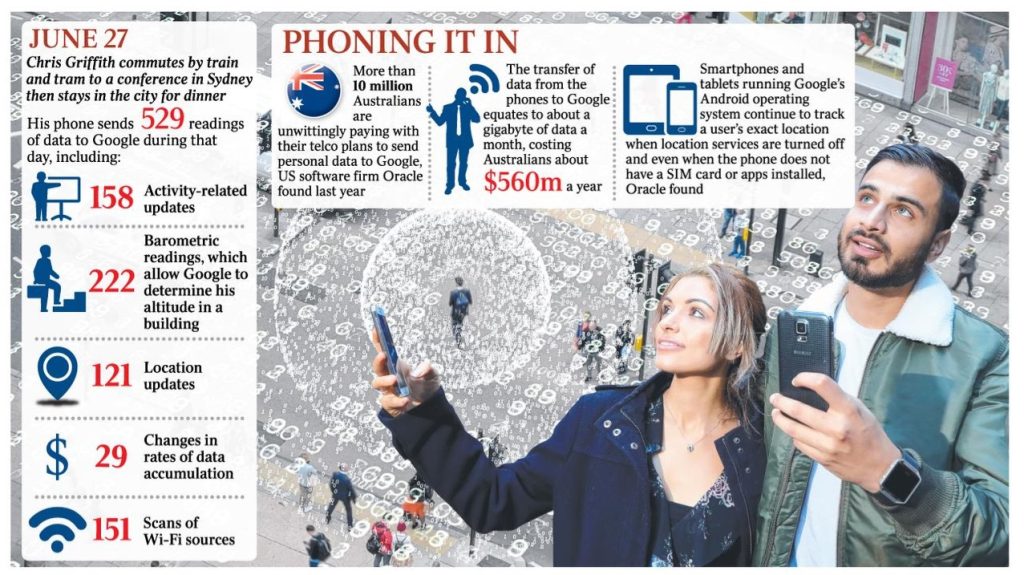

On June 27 I commuted by train and tram to a conference, then stayed in the city for dinner. The phone sent 529 readings of data to Google. Of that, 158 were activity-related, 222 were barometric readings, 121 were locations, 29 were about changes in rates of data accumulation and 151 were scans of wi-fi sources.

Wi-fi window

A small sample of the “fire hose” of data gathered from one of two Android phones, Chuck and Diane. Wi-Fi identification data has been blurred, but each row can display the ID of many Wi-Fi access points in an area.

The data included the Mac addresses of wi-fi access points within buildings I visited that day, including the conference centre and my work, the frequency of the wi-fi device and signal strength. This offers a more accurate determination of where you are indoors than can be gleaned from GPS and cellular data.

Knowing your indoor location may not bother you when shopping, but triangulating the proximity of employees to different wi-fi access points at work and using signal strengths could help work out who is in contact with whom. Google may not do this, but the data is there.

Google does ask permission to collect wi-fi data when you set up your phone. It’s one of the first permission requests on a new device. But Google doesn’t ask your workplace if it is OK that your phone records their wi-fi router details. It asks you for permission for your phone to snoop on Google’s behalf. Just one visitor to an office location is enough for Google to glean details of wi-fi devices within it. Chuck and Diane collected such data from offices I visited during the test.

Data collection doesn’t stop at night when you relax at home and go to bed. On the night of June 24, between 10pm and 6am, when I was asleep at home, the phones sent Google 164 pieces of information about my environment. There were barometer readings, wi-fi listings of my neighbours, and observations such as “still with confidence”. Being “observed” overnight made me feel like I had been monitored by a night nurse. The data was grossly disproportionate to any Android support I needed as a user.

There were “check-in records” that tied together details of phones such as the model, user email address, device identifier, the phone’s wi-fi Mac address and Android ID. No anonymity. I could view a comprehensive history of my connection to mobile phone towers and wi-fi access points throughout the day.

Overriding airplane mode

There’s evidence that phones accumulate statistics even when in airplane mode. On June 27, Diana, in airplane mode, recorded my location and transmitted it the next day when it reconnected. The location was correct.

Each day the phones were assessing my movements, whether I was “still”, “inVehicle”, “onBicycle” or “unknown”. The data shows whether the phones are charging and their battery level. Each snippet includes a confidence level of whether the movement assessment is correct. Not all of them are correct, however.

If you consider the enormous data collected by just one phone, it’s unfathomable to imagine how Google meaningfully handles data it receives each day from 2.5 billion Android devices globally. The flow of information into the tech giant is astronomical.

But Google would have the data needed to piece together the location of people who are indoors and outside based on its knowledge of every wi-fi device on the planet. That’s before we add in GPS and cellular tracking.

This data collection is symptomatic of what’s happening across the world. The UN Economic Commission for Europe estimates that by next year the total data generated globally will be 40 zettabytes (40 billion terabytes, or 40,000 billion gigabytes). According to IBM, 90 per cent of the world’s data was generated in the past two years and we generate the equivalent of all the data captured in 2002 every two days.

Much of the data in future will be from Internet of Things sensors, but there’s lots of personal data too. The ACCC report includes a 130-page chapter that focuses on whether consumers can make informed choices on how digital platforms collect, use and disclose their personal information and user data.

The chapter lists 30 categories of data Google collects about people, as at January this year. They include not only name, birthday, phone number and email address, but also search history, messages, phone calls, comments you post, and mobile network information. That’s the data that’s declared.

Gagging Google

It is paramount that we address whether these other types of data can be even generated let alone retained in identifiable or unidentifiable form. Could 21st-century life go on, if Google wasn’t constantly collecting data from your phone every instant of the day? Can this data fire hose be turned off?

The ACCC report is an incredibly comprehensive take on this out-of-control collection of data, but there’s a danger the issue will degenerate into a talk fest rather than action.

This data fire hose has been highlighted before, but we decided to conduct our own test of it here in Australia. We used phones and a data analysis package supplied by US firm Oracle, which is in long-term litigation with Google over the ownership and use of the Java programming language. But the analysis was our own.

The ACCC last year began an investigation into data collection including this Google data fire hose, but the report says the investigations are continuing. The ACCC is yet to form a view it but plans to conclude the investigations later this year.

So what happens next? There’s a suggestion that we regulate the big tech giants, but the easier path could be to regulate the types of personal data that can be collected, how data is used, the right to veto the use of your data for purposes other than originally intended, and the right to demand its deletion. The giants would be obliged to comprehensively reveal the data they glean from you, your phone and other devices.

The US Federal Trade Commission’s $US5 billion ($7.24bn) fine of Facebook this month shows that the tech giants can be held to account on how they control the use of consumers’ personal information. It’s not a hopeless task.

Deleting data

The better path is genuine co-operation to make managing personal privacy easier. For example, Google recently implemented auto-delete controls where you can opt to have your data deleted after three months or 18 months.

This auto-delete feature is a good idea and it exists on Android phones I use. However, it is buried. You choose Settings, Google Services, Google Account, Privacy and Personalisation, and Activity Controls to even find it. You then go into web & app activity, or location history, to access auto-delete controls. I’d bet less than 1 per cent of users know about it, let alone how to access it.

Auto-delete controls allow you to share some information for a period of time without spending your life managing that data thereafter. But Google should include a dedicated privacy app so that accessing privacy controls including auto-delete is simple. You shouldn’t have to go through a labyrinth of menu choices in the Settings app to find them.

Apple has got its act together on this with prompts that let users give permission for use of their location for a single session. The application has to request your location afresh the next time around. Data permissions are transient. Apple is offering periodic alerts that show the kind of locations being shared with an app, so you can decide whether to allow the app continued access.

But you should not have to share data in the first place. The policy should be opt-in, rather than requiring users to opt out.

Tech companies also should address the issue of users feeling bullied into agreeing to share data, and a barrage of menu obstacles and warnings that dissuade them from saying no. In the end, lots of practical software adjustments may assist consumers more than months of longwinded theoretical discussion that end up as hot air.

We need to turn off the unbelievable continuous streaming of data from our phones as revealed by Chuck and Diane. I’d say leave fire hoses to fire trucks. This is a form of madness that should end today.

- Google later said it did not collect data at this intensity.

Published in The Australian newspaper.