Social media and artificial intelligence will derail our democratic elections in the 2020s if left unabated.

New technologies are becoming available that amplify the misinformation and confusion that social media already unleashes.

We’ve seen fake news and state-sponsored sites designed to spread misinformation. Now we are dealing with fake videos that show politicians and celebrities mouthing words they never said.

Malevolent countries soon will be able to saturate the web and social media with false stories written by machines. This technology is in the wings. The number of countries involved in the organised production of fake news is spreading beyond Russia and China to states such as Iran.

Back home, there’s the increasing capability of all sides of politics to finetune online misinformation campaigns that target just a few hundred voters — campaigns with lies that can damage political opponents who may never hear about it and therefore can’t rebut.

Complicating the conundrum is the reluctance of social media sites to accept responsibility for mistruths on their platforms. Facebook says it won’t even fact-check questionable material.

This leaves the public making democratic choices based on an avalanche of computer-generated fake information. Unless people choose their news sources carefully, and properly check important information, we’re heading for mass confusion.

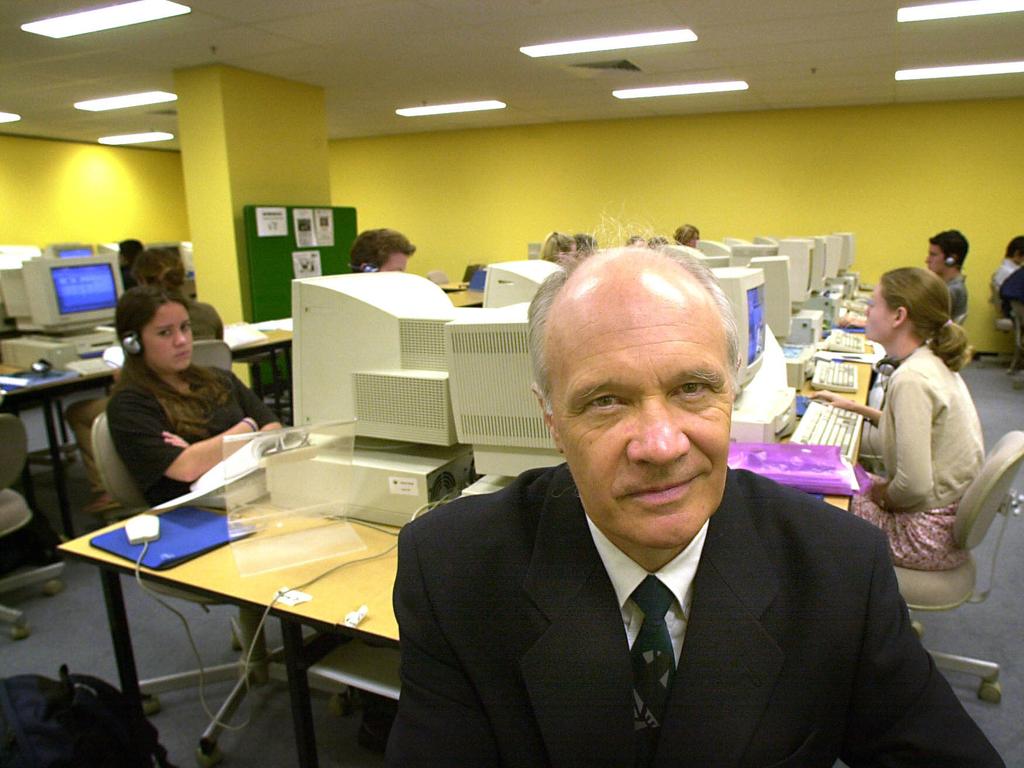

“I think that is a worry because of the capacity for people to be influenced,” says journalism academic John Henningham, director of Brisbane-based online journalism college Jschool. “This is what’s different — specific campaigns to tell lies, not just matters of exaggeration and emphasis and so on.”

Henningham says political parties face a problem keeping up with the “lies” cast against them. “It would take a lot of their attention away from the message they’re trying to get out if they have to spend their time trying to rebut this source material and then convince people that their rebuttals are themselves accurate and not another form of falsity.”

In Australia there’s nothing to stop this juggernaut rolling on unabated with all sides of politics, Liberal, Labor, the Greens, everyone, affected.

Concern about “deep fake” videos has been mounting. It wasn’t an issue at the time of the 2016 US presidential election but is now. In a recent blog Australia’s CSIRO warns of the rise in “online deceit” and says while the public previously didn’t have the tools to create deep-fake videos, this is changing.

CSIRO agency Data61 gives the example of Snapchat’s introduction of a gender swap filter as an example. “The cost of a free download is all it takes for a Snapchat user to appear as someone else,” it says

Deep fakes overwhelmingly involve pornography — cleverly doctored video showing celebrities and public figures involved in sex acts. Deeptrace, which monitors this trend, found that non-consensual deep-fake pornography accounts for 96 per cent of deep-fake videos online, with four websites receiving more than 134 million views of more than 14,000 deep-fake videos, targeting hundreds of female celebrities worldwide.

In Australia, lawyer and WA Young Australian of the Year Noelle Martin went public with how she was the target of deep-fake predators who turned her photos into porn and created two videos of her performing sex acts. She says she felt “sick, disgusted and humiliated” by the material, which nearly ruined her life. But the trauma was amplified by the difficulty of trying to take action against the sources.

“This is one of the challenges we face in addressing this issue, particularly where perpetrators are overseas,” she says.

On the political front there are fears that deep fakes will have a profound impact on ballots such as the December 12 British general election. The tactics that emerged in 2016 US election — Russian meddling through its Internet Research Agency and the Cambridge Analytica scandal involving the personal data of up to 87 million users — first became apparent in the Brexit referendum five months earlier.

Advances in AI and machine learning and refinements of targeted campaigning techniques make the situation ahead worse.

In Gabon in January, a video suspected to be fake showing an ill President Ali Bongo Ondimba led to an attempted military coup a week later. In Britain, shadow Brexit secretary Keir Starmer was the victim of a doctored video showing him lost for words when asked about Labour’s plan for Brexit. He had actually given a detailed response.

In the US, mounting concern has seen some action from the tech giants. Google parent Alphabet says it will prohibit deep fakes in political and other ads, while Twitter is considering identifying manipulated photos, video and audio shared on its platform.

READ MORE: New techniques for fake video and audio | NewsGuard shines a red light on fake news sources

The Wall Street Journal reports that Facebook, Microsoft and Amazon are working with US universities to run a Deep Fake Detection Challenge starting next month. It says the Pentagon is studying deep fakes out of concern that military planners could be fooled into making bad decisions if altered images aren’t detected.

Research and resources will be needed to combat the volume of deep fake material expected to go online. It’s not just video. The Wall Street Journal also reports that it is becoming easier for machines to produce real-sounding and made-up news articles using new tools powered by artificial intelligence.

“Many of the researchers who developed the technology, and people who have studied it, fear that as such tools get more advanced, they could spread misinformation or advance a political agenda,” the newspaper reports.

Another issue is the exposure of political operatives working within social media organisations. There seems to be little monitoring of their activities.

In 2016, James Barnes, a lifelong Republican who worked at Facebook, helped the Trump campaign use Facebook’s tools to extend its reach. He has changed sides and says he will help the Democrats next year. He has left Facebook but his former role is worrying.

The big tech firms also shirk their responsibilities in handling information. ACTU secretary Sally McManus recently complained that she simply didn’t write a photoshopped tweet where she says the ACTU passed an inheritance tax, but Facebook refuses to take it down. Whether you agree with McManus’s views isn’t the point; the fact Facebook won’t act against blatant fakes is a problem for everyone.

At least Google is signalling a preparedness to do more. “That’s why we’re limiting election ads audience targeting to the following general categories: age, gender, and general location (postcode level),” it says. Google says political advertisers still can serve ads to people reading or watching a story about, say, the economy, but ads that target voters with other variables, such as party affiliation, are out. However, social media firms are between a rock and a hard place when attempting to clean out false claims. The problem is: where does truth end and a lie begin?

Henningham says: “It’s a very difficult line to draw. I think even people who are opposed to censorship as their dominant position still believe in censorship when it comes to deeply offensive images and criminal activity and so on. So, some sort of line must be drawn.”

He warns that in the end, no one will believe anyone if this situation is left to fester.

The federal government says it is aware of this problem. “The government is conscious of the challenge posed by the spread and amplification of disinformation online,” Communications, Cyber Safety and the Arts Minister Paul Fletcher says. “Maintaining a healthy public discourse is of central importance to democracies such as Australia.”

He says Australians need to be equipped with the tools and skills to be discerning consumers in today’s digital media environment and that the issue of digital media literacy has been raised by the final report of the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission’s digital platforms inquiry, which the government is considering.

Australia at least will be able to watch developments with this technology at British and US elections before we go the polls, but political misinformation online at elections must be tackled.

Otherwise, if you think Labor’s “Mediscare” campaign and Clive Palmer’s and the Coalition’s campaign on Labor “death duties” were damaging, wait for the campaigns at the next federal poll.

Published in The Australian newspaper